Perceptions by Regulators and Operators Regarding Retail Bare Hand Contact Prohibition in Oregon

Gemedi Geleto

Registered Environmental Health Specialist

Washington County Health & Human Services, Environmental Health

International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI)

2015 - 2016 Fellow in Applied Science, Law, and Policy: Fellowship in Food Protection

Author Note

Gemedi Geleto, Registered Environmental Health Specialist, Washington County Oregon Health & Human Services, Environmental Health.

This research was conducted as part of the International Food Protection Training Institute’s Fellowship in Food Protection, Cohort V.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Gemedi Geleto. Washington County Oregon Health & Human Services, 155 N. First Ave., Suite 160, Hillsboro, OR 97124-3072. Email: Gemedi_Geleto@co.washington.or.us

Abstract

This exploratory study examined the perceptions of food safety regulators and food service establishment operators regarding the prohibition of bare hand contact with ready-to-eat (RTE) foods in an area encompassing approximately 40% of Oregon’s population. A nine-question survey was sent in 2015 to 142 local food regulators and over 1286 food service establishments in Deschutes, Washington, and Multnomah counties; the study received 217 responses. Study findings included low levels of belief in bare hand contact as a public health problem by operators (27%), but also by some regulators (67%); both regulators (33%) and operators (65%) were opposed to prohibiting bare hand contact; and roughly half of both groups believed that the only way to limit bare hand contact is by prohibition. Study recommendations include the adoption of a no bare hand contact provision given wide-spread evidence of risk and only limited problems in implementation; a need for improved education of operators and regulators regarding bare hand risks and risk reduction methods; and encouragement for operators to adopt alternatives to bare hand contact.

Keywords: bare hand contact prohibition, bare hand contact risks, food safety regulators, food service, Oregon Health Authority, public health

Background

Bare hand contact with food is one of the frequent contributors to foodborne illness outbreaks in the U.S. (Green et al., 2006). Sixty percent of reported foodborne illness outbreaks occurred in restaurants (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013) and 89% of these outbreaks were attributed to employee contamination (CDC, 2011a, 2011b). Contamination can increase by as much as 50% where bare hand contact with foods is not prohibited (CDC, 2013). Bare hand prohibition varies among states. A U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Regional Food Specialist, shared internal National Restaurant Association (NRA) data showing that 10 states permit bare hand contact, 12 states prohibit bare hand contact, and the other 28 states allow bare hand contact if a food service operator has a variance. The FDA defines variance as a written document issued by the regulatory authority that authorizes a modification of Model Food Code guidelines if, in the opinion of the regulatory authority, a health hazard will not result from the modification (FDA, 2009).

The Oregon Health Authority did not adopt a bare hand prohibition in 2012 during the Food Code adoption process due to industry pressure (LeTrent, 2012). Anecdotal evidence from food safety regulators suggests that Oregon food service operators do not understand that bare hand contact is a significant contributor of foodborne outbreaks (Russell, 2012, June 28). In email communications from an Oregon Health Division regulatory official and a Washington County Oregon regulatory official, unpublished Oregon outbreak database report from 2011-2014, shows that bare hand contact was a contributing factor in 11 foodborne outbreaks involving 302 people, nine hospitalizations, and one death.

Problem Statement

The Oregon Health Authority’s adoption of the 2009 FDA Food Code did not include the bare hand contact prohibition related to ready-to-eat (RTE) foods despite national evidence that bare hand contact is a contributing factor to foodborne illness outbreaks in Oregon.

Research Questions

1. Why do food service operators oppose a bare hand contact prohibition?

2. What actions can be taken to avoid bare hand contact within regulated industry without a bare hand contact prohibition rule?

3. How can regulators address industry concerns regarding a bare hand contact prohibition rule?

Methodology

A nine-item electronic survey was developed with the assistance of experienced regulators. The survey included three demographic questions followed by six questions related to bare hand contact with RTE foods in food service establishments. The questions were: 1) What does the term “bare hand contact” with RTE foods mean to you? 2) Do you think “bare hand contact” with RTE foods is a public health problem? 3) Is “bare hand contact” with RTE foods a major contributing factor in foodborne illness outbreaks? 4) Should the Health Department prohibit “bare hand contact” with RTE foods? 5) A. Would you have concern if the Health Department prohibited “bare hand contact” with RTE foods? B. What would concern you? 6) A. Are there ways to limit “bare hand contact” with RTE foods without a stringent “no bare hand contact” requirement by the Health Department? B. Please write the best ways to limit “bare hand contact” with RTE foods.

After a pilot test, the survey was sent to operators working in five types of food service establishments: fast food restaurants, sit-down restaurants, mobile food units, national chain restaurants, and regional chain restaurants. Distribution was accomplished with assistance from the Environmental Health Departments in three counties during November and December 2015: Washington County sent the survey to 526 establishments; Deschutes County sent the survey to approximately 700 establishments; and Multnomah County posted a link to the survey on its web site. These counties comprise roughly 40% of Oregon’s population, a wide urban-rural mix, and a great variety of food service establishments. The survey was also sent to 142 county Environmental Health Department regulators in the entire State of Oregon who supervise or carry out inspections of food service establishments. Responses to the six questions related to bare hand contact were analyzed in order to address the research questions given above.

Results

A total of 165 operator responses were received; 98 from Washington; 52 from Deschutes; and 31 from Multnomah Counties. Sixteen of the respondents had restaurants both in Washington and Multnomah Counties. Of those 16 respondents, four were national chain restaurants. Two of the respondents in both Multnomah and Washington Counties owned regional chain restaurants. Three of the respondents operated mobile food units in both Multnomah and Washington Counties. A total of 46 regulator responses were received representing 13 of Oregon’s 36 counties. Three regulator responses came from county epidemiologists. The results are summarized below.

The survey questions began by examining the meaning of the term “no bare hand contact.” For both groups, “no bare hand contact” was associated with “no glove use.” The study then used two parallel questions to assess the respondents’ perceptions of bare hand contact risk by asking whether “bare hand contact” is a public health problem and whether “bare hand contact” is a major contributing factor in foodborne illness outbreaks (Table 1). Regulators were positive about both (67% responded affirmatively to each question), but the majority of operators (56% and 52%) believed the opposite. However, of interest is that the national chain restaurant operators were more positive (50% and 44%) than other types of operators regarding whether bare hand contact is a public health problem. The survey then sought to determine whether the respondents believed that bare hand contact with RTE foods should be prohibited. In general, the responses indicated that barely half the regulators and less than one fourth of the operators support a prohibition.

The study then sought to determine if the respondents would have concerns if the Health Department prohibited bare hand contact with RTE foods. Overall, operators were more concerned (56%) about such a prohibition than regulators (28%). Both operators and regulators believed glove use would provide food workers with a false sense of security and would result in improper handwashing. Additionally, the operators cited cost and the environmental impact of glove use as concerns related to a bare hand contact prohibition more often than the regulators. When compared with other operators, regulators and national chain operators were less concerned with a bare hand contact prohibition (Table 2).

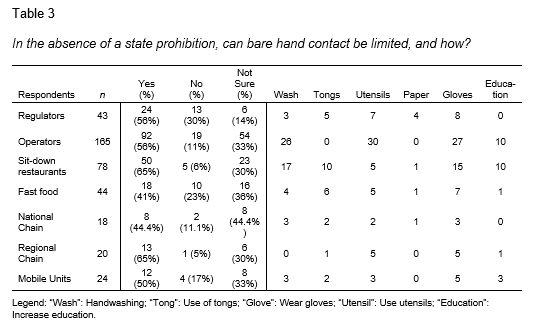

The survey concluded with a question that asked for ways in which operators might limit bare hand contact in the absence of a state prohibition. Roughly half of the regulators and the operators thought that operators could do so (Table 3). Operators reiterated the importance of handwashing and education when asked about how to limit bare hand contact in the absence of a bare hand contact prohibition rule. While both groups mentioned handwashing and use of gloves and utensils, the operators frequently mentioned use of gloves and education while the regulators did not.

Conclusion

The study concluded that there were three primary reasons for opposition to a prohibition on bare hand contact in food service establishments. First, there was a lack of acceptance that bare hand contact with RTE food is a public health problem. Second, the survey participants expressed concern that glove use would diminish handwashing by food workers and that gloves would not provide adequate public health protection. Third, the survey participants incorrectly assumed that “no bare hand contact” with RTE food meant that the Health Department was going to mandate glove use.

The study also concluded that bare hand contact can only be limited in part without a state rule. The operators believed that educating food workers on alternative methods of handling food would help limit bare hand contact. The suggested alternatives to bare hand contact included the use of wax paper, utensils, tongs, and gloves. Regulators also believed that bare hand contact could be limited by employing alternative methods. However, a significant number of operators and regulators remained opposed to glove use. The operators’ perception that handwashing was adequate to protect public health, combined with their fear of food workers’ false sense of protection when using gloves, led the operators to oppose glove use. The regulators were opposed to glove use for a slightly different reason: the observation of improper glove use by operators during inspection.

Recommendations

The Oregon Health Authority should adopt a “no bare hand contact” provision given the widespread evidence of foodborne illness associated with bare hand contact nationally and in Oregon, and the limited number and type of problems identified by operators in this study resulting from adoption of such a prohibition.

The Oregon Health Authority should improve the education of operators regarding the risks associated with bare hand contact, along with methods (such as glove use) to reduce those risks, especially given the limited knowledge among operators of those risks and methods found in this study.

Regulators can find ways to address concerns about glove use. Regulators can educate operators on the availability of cost effective and biodegradable gloves. In fact, the Oregon Health Authority identified cost effective gloves during the 2012 Food Code adoption process. The cost of gloves can range from one-tenth of one cent to 10 cents each depending upon the type (Fussell, 2012). Additionally, regulators can help operators understand that there are alternatives to glove use if the operators choose not to use gloves.

The Oregon Health Authority should provide training for regulators to increase their understanding of bare hand contact risks.

The Oregon Health Authority should encourage the food service industry to find and apply more alternatives to bare hand contact when handling RTE foods given the limited number of alternatives identified by respondents in this study.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to many people who have helped make this project possible. First, I would like to thank the International Food Protection Training Institute (IFPTI) for providing me with the opportunity to participate in this Fellowship Program. I would like to thank the entire IFPTI staff including the subject matter experts and the mentors. I especially want to thank my mentor, Dan Sowards, for his guidance and invaluable input. A special thanks to Dr. Paul Dezendorf for his expertise and very important feedback. Second, I would like to thank Environmental Health supervisors Eric Mone, Jeffrey Martin, Frank Brown, and Jon Kawaguchi of Deschutes, Multnomah, and Washington Counties for their input and for allowing their establishments to participate in the survey. I especially want to thank Washington County Oregon Environmental Health supervisors Frank Brown and Jon Kawaguchi for their unwavering support and for allowing me to complete the program. A special thanks to Washington County Oregon Epidemiologist Eva Hewes for her important input. Third, I want to thank all of the participants in the survey. Finally, I want to thank all of the Cohort V Fellows for their friendship and encouragement.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Environmental Health, Division of Emergency and Environmental Health Services. (2011a). Food worker handwashing and food preparation: EHS-Net study findings and recommendations (CDC Publication No. CS224881-C). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/ehsnet/plain_language/food-worker-handwashing-food-preparation.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Environmental Health, Division of Emergency and Environmental Health Services. (2011b). Food worker handwashing and restaurant factors: EHS-Net study findings and recommendations (CDC Publication No. CS224881-B). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/ehsnet/plain_language/food-worker-handwashing-restaurant-factors.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks, United States, 2013: Annual report. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2015.

Fussell, J. (2012). Presiding hearing officer’s report on rulemaking and public comment period: Adoption of 2009 FDA Food Code. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Health Authority.

Green, L. R., Radke, V., Mason, R., Bushnell, L., Reimann, D. W., Mack, J. C., . . . Selman, C. A. (2006). Factors related to food worker hand hygiene practices. Journal of Food Protection, 7(3), 661-666. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/ehsnet/docs/jfp_food_worker_hand_hygiene.pdf

LeTrent, S. (2012, July 12). Oregon dismisses glove requirement for restaurant workers. CNN/Eatocracy. Retrieved from http://eatocracy.cnn.com/2012/07/12/oregon-dismisses-glove-requirement-for-restaurant-workers/

Russell, M. (2012, June 28). Oregon restaurateurs fight new state rule banning bare hand contact with food. The Oregonian/OregonLive. Retrieved from http://www.oregonlive.com/dining/index.ssf/2012/06/oregon_restaurateurs_fight_new.html

U. S. Food and Drug Administration. (2009). Food Code: 2009 Recommendations of the United States Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/GuidanceRegulation/UCM189448.pdf