Active Managerial Control: Factors Influencing How Environmental Health Specialists Mark Supervision Compliance Status in Retail Food Service Establishments

Lauren Baker-Newton, MPH, REHS

Environmental Health Specialist V – Chatham County Health Department

Abstract

Active managerial control (AMC), under the direction of the person-in-charge (PIC), takes a preventive approach to managing risk factors during day-to-day retail food service operations. While conducting routine inspections, environmental health specialists (EHS) are responsible for determining if the operator is practicing AMC by evaluating the systems that the PIC has put into practice regarding the oversight and routine monitoring of risk factors. The purpose of this study was to determine the contributing factors influencing how EHS assess AMC and mark supervision compliance status when risk-factor violations were observed. To determine the contributing factors, this study used the review of routine retail food service inspections, along with surveys distributed to environmental health personnel throughout Georgia. The study found that EHS held differing views regarding AMC assessment, which resulted in varying interpretations for pattern of noncompliance and obvious failure of the PIC to ensure risk factor compliance. The varying interpretations ultimately led to uncertainty among EHS attributing to the underassessment of AMC. As a result of the findings the following recommendations were made in order to increase consistency and standardization among EHS: amendment of Georgia’s marking guide instructions to include definitions for pattern of noncompliance and obvious failure of the PIC to ensure compliance; creation of supplemental job aids explaining the proper assessment of AMC; evaluation of current training methods for effectiveness; and inclusion of an evaluation of AMC assessment as a part of district uniform inspection audits.

Key words: Active managerial control, risk factor, person-in-charge, compliance, environmental health specialist

Active Managerial Control: Factors Influencing How Environmental Health Specialists Mark Supervision Compliance Status in Retail Food Service Establishments

Background

Foodborne illness is defined as an illness caused by eating foods that have been contaminated with harmful microorganisms (Marks, 2021). According to the Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) 2017 Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance Report, “Restaurants were linked to outbreaks more often than any other place where food was prepared. Restaurants were associated with 489 outbreaks, accounting for 64% of outbreaks that had a single location where food was prepared” (CDC, 2019).

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has reported that, in order to effectively reduce major foodborne illness risk factors in retail establishments, a food service business should use food safety management systems (FSMS), however in a 2018 report, it was determined that less than 11% of audited food service businesses were using a well-documented FSMS, thus implying a lack of active managerial control (King, 2020).

Active managerial control takes a preventive approach to managing risk factors during day-to-day operations. Ideally, risk-factor management is coordinated and overseen by the person in charge, with supervisory responsibility, who has the authority to direct processes and corrective actions within the establishment. The PIC is more than simply the liaison between the facility and the EHS during the inspection; the role of the PIC is an integral one for the operation. The PIC is responsible for ensuring the risk of foodborne illnesses is reduced by implementing safe and proper food handling practices.

While food safety is the common goal of operators and regulators of retail food service establishments, regulatory oversight has been predominantly reactive in that “inspections have emphasized the recognition and correction of risk-factor violations that exist at the time of the inspection” (FDA, 2017). To effectively assess AMC, regulatory inspections must be proactive by using an inspection process designed to evaluate the implementation of FSMS designed to ensure that risk reduction practices are in place at all times, and the degree of AMC that food service operators have over foodborne illness risk factors (FDA, 2017). During an inspection, an EHS is responsible for determining if the operator is practicing AMC by evaluating the systems that the PIC has put into practice regarding oversight and routine monitoring of the duties listed in Georgia Department of Public Health Food Service Rules and Regulations. This decision is based upon discussion with the PIC and verified through observation. Per Georgia’s Instructions for Marking the Food Service Inspection Report form, when “there is a pattern of non-compliance and obvious failure of the PIC to ensure compliance,” then PIC duties should be marked out of compliance (DPH, 2019). Therefore, a PIC violation is not a simple observation; it is a combination of conditions and interview findings that need to be evaluated and assessed by an EHS.

In this researcher’s role as a district-standard trainer for Georgia’s Coastal Health District, reoccurring observations have been made where PIC performance of duties has been identified as in compliance though multiple risk factor violations have been documented. While the assessment of AMC does require an EHS to use best judgment, the overall evaluation of the PIC's ability to ensure risk factor compliance should be objective, unbiased, and based on concrete observations and conversations held with the PIC during inspections. This recurring observation calls into question the factors that influence how EHS evaluate AMC, and the point at which AMC is marked out of compliance. While risk factor violations are mandated to be corrected within a specified amount of time, often the corrective actions offer short-term compliance. Furthermore, there is often little to no evidence that the operator has the necessary management systems for continued control of the risk. This observation also is important because it signifies a missed opportunity for the EHS to educate the PIC and assist with the development of effective AMC systems, ultimately contributing to the continued presence of foodborne illness risk factors.

Problem Statement

The contributing factors influencing how active managerial control violations are reported by environmental health specialists in Georgia during routine inspections of retail establishments are unknown.

Research Questions

1. What association does inspection data show between risk factor violations and person in charge performance of duties compliance status?

2. What factors influence how an environmental health manger documents compliance status regarding the fulfillment of the duties of the person in charge when risk factor violations are observed during routine inspections?

Methodology

In Part one, Digital Health Department (DHD), the statewide electronic system used to manage food service inspection data entry, was used to identify all routine food service inspections conducted by each EHS during the period from January 1, 2018, through December 31, 2020. The foodborne illness risk-factor section of the inspection reports was then reviewed, and the frequency at which both AMC and risk factors were marked out of compliance was tabulated.

In Part two, a Microsoft Forms survey was created and distributed statewide to district environmental health mangers (DEHM) and district standard trainers (DST) via email, with a request to forward to EHS with food service inspection responsibilities within their respective district. The survey used closed-ended questions and sought to determine the following: how EHS were trained regarding the assessment AMC when EHS marked PIC performance of duties out of compliance; how EHS defined both pattern of noncompliance and obvious failure of the PIC; the factors contributing toward uncertainty during AMC assessment; and actions EHS believed would better prepare them to assess AMC.

Results

Between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2020, a total of 115,532 routine inspections were conducted throughout the state of Georgia. EHS documented a total of 109,448 risk-factor violations, during a total of 57,968 routine inspections, which accounted for 50% of the routine inspections conducted. EHS also indicated that follow-up inspections, which are conducted after a routine inspection resulting in a “C” or “U” letter grade representing marginal or unsatisfactory compliance, were required on 19% of inspections conducted. Additionally, EHS observed a total of 31,544 repeat violations with an average of 12% of violations being marked as “repeat” across the specified time frame. Inspection data also showed a 2% increase of repeat violations between 2018 and 2020, however, both tabulations regarding repeat violations included both risk-factor and good retail practice violations which collectively totaled 254,696 violations. The above-mentioned initial and repeat violations resulted in AMC being marked as a violation during 2% (2,265) of routine inspections, on average, during the specified timeframe.

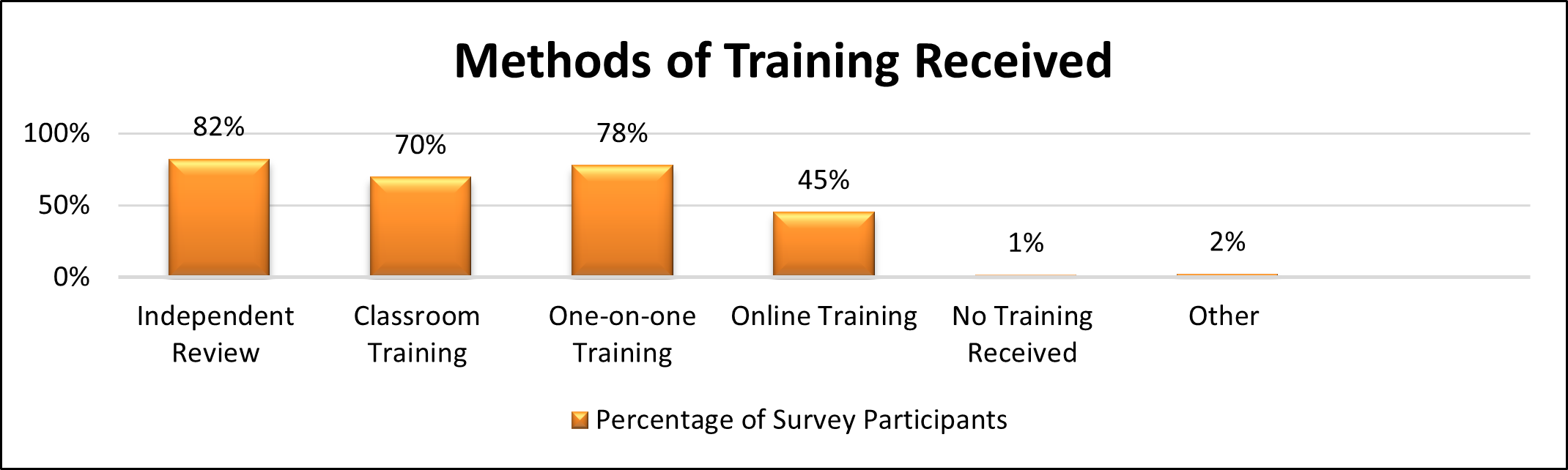

A total of 135 replies were received in response to the survey distributed. Participants included a combination of environmental health specialists, environmental health county managers, district environmental health managers, district standard trainers, and food program consultants. The survey determined the method of EHS multimodal training regarding the assessment of AMC (Graph 1). The most predominately identified modes of training included the independent review of Georgia’s food service rules and regulations and the marking instructions; classroom training; and one-on-one training with 82% (111), 70% (94) and 78% (105) of participants selecting the options respectively.

Graph 1

Methods of Training Received

Based on the survey responses received, 59% of survey participants (79) identified marking active managerial control, item 1-2A, “out of compliance” when the PIC was unable to describe the facility’s food safety management procedures, and there were more than two risk-factor violations. The second most prevalent option selected, which was chosen by 43% of survey participants (58), indicated marking “active managerial control out of compliance” when the PIC was unable to describe the facility’s food safety management procedures, regardless of how many risk-factor violations were present.

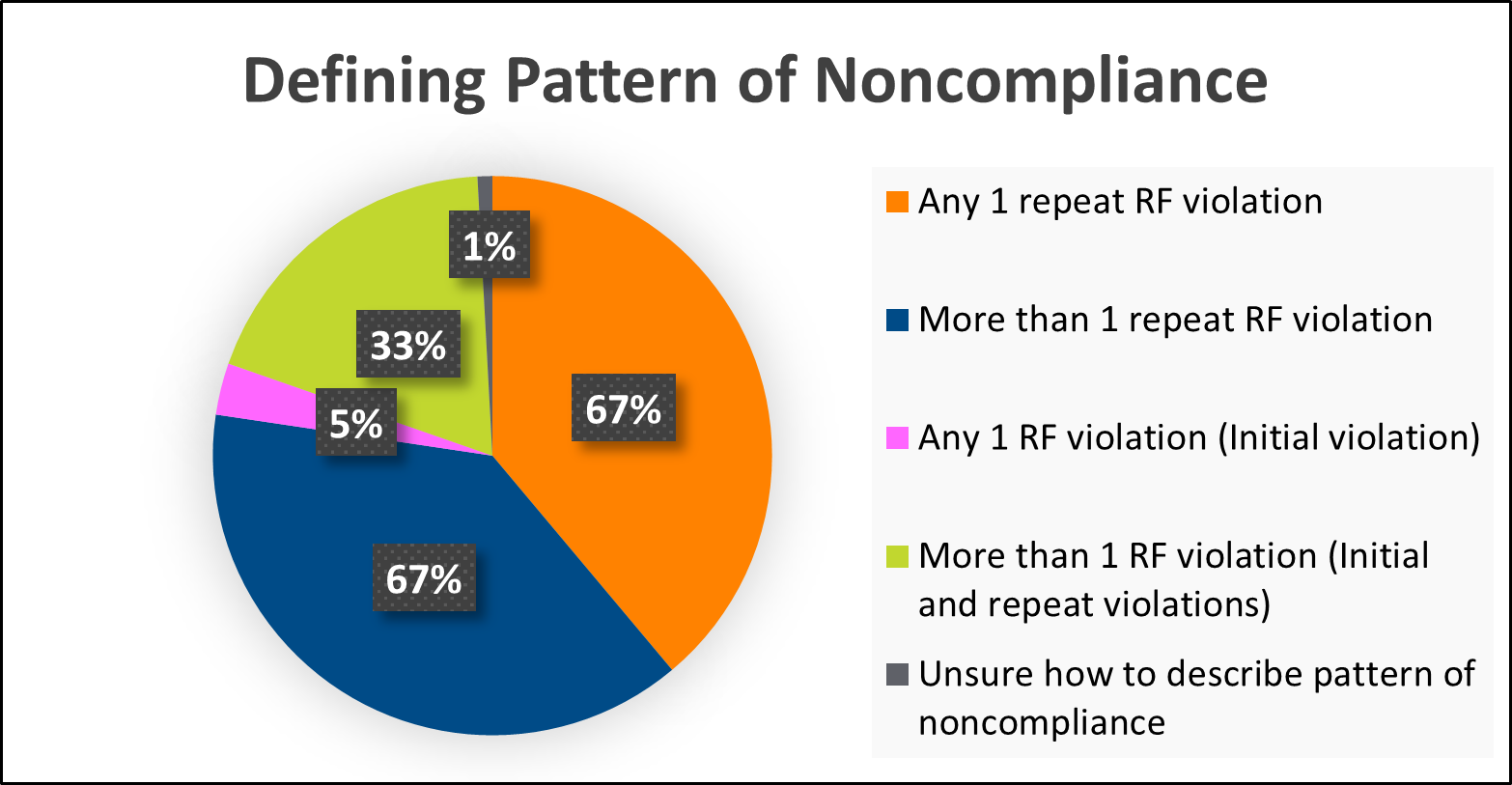

Regarding what signified a pattern of noncompliance during routine inspections, survey results identified that EHS held varying definitions (Graph 2). Ninety-one survey responses (67%) included defining a pattern of noncompliance as any 1 repeat risk factor violation observed during a routine inspection. There also were 90 survey responses (67%) that included defining pattern of noncompliance as observing more than one repeat violation.

Graph 2

Defining Pattern of Noncompliance

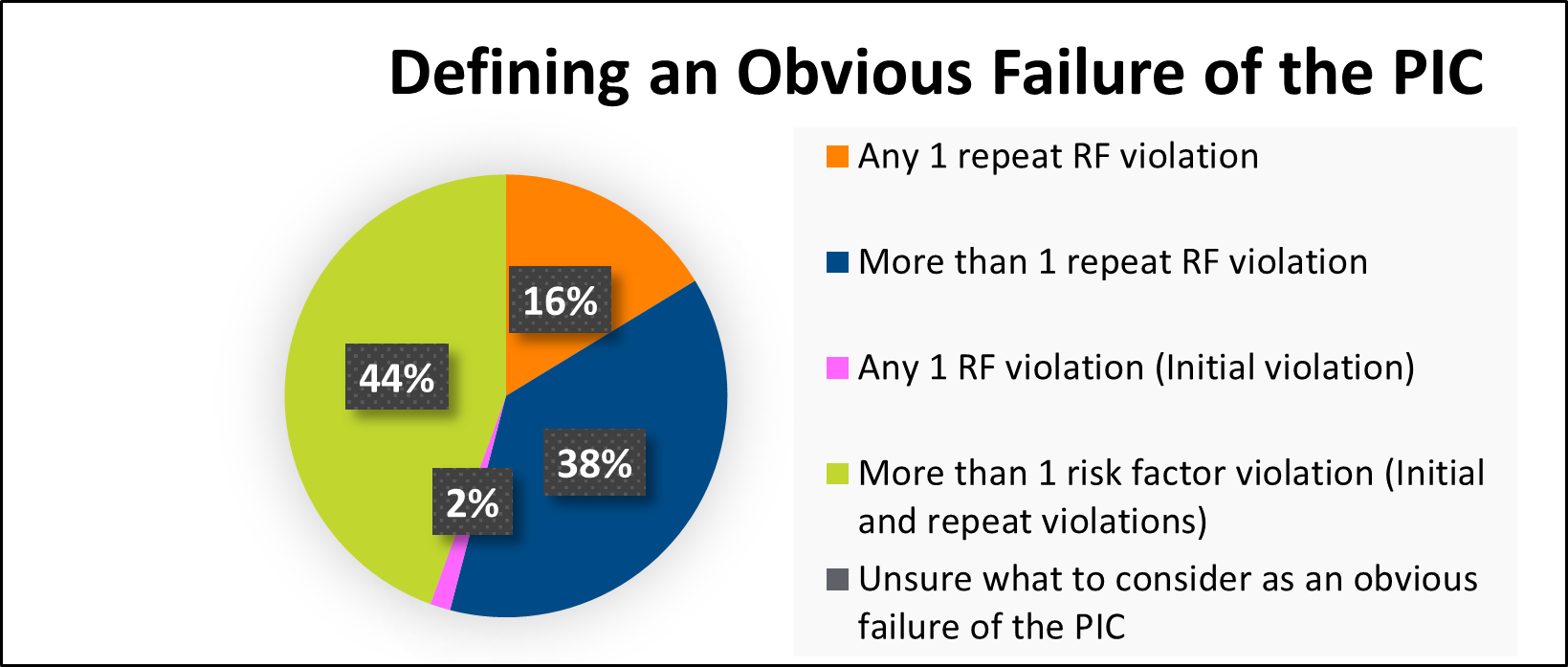

Regarding what represented an “obvious failure of the PIC,” the survey revealed that EHS held different opinions regarding the observations coinciding with an obvious failure of the PIC to fulfill their responsibilities during routine inspections (Graph 3). Based on survey responses, 44% of survey participants (60) identified defining an “obvious failure of the PIC” as the presence of more than one risk factor violation, while 38% of survey participants (51) identified defining an “obvious failure of the PIC” as the presence of more than one repeat risk-factor violation.

Graph 3

Defining An Obvious Failure of the PIC

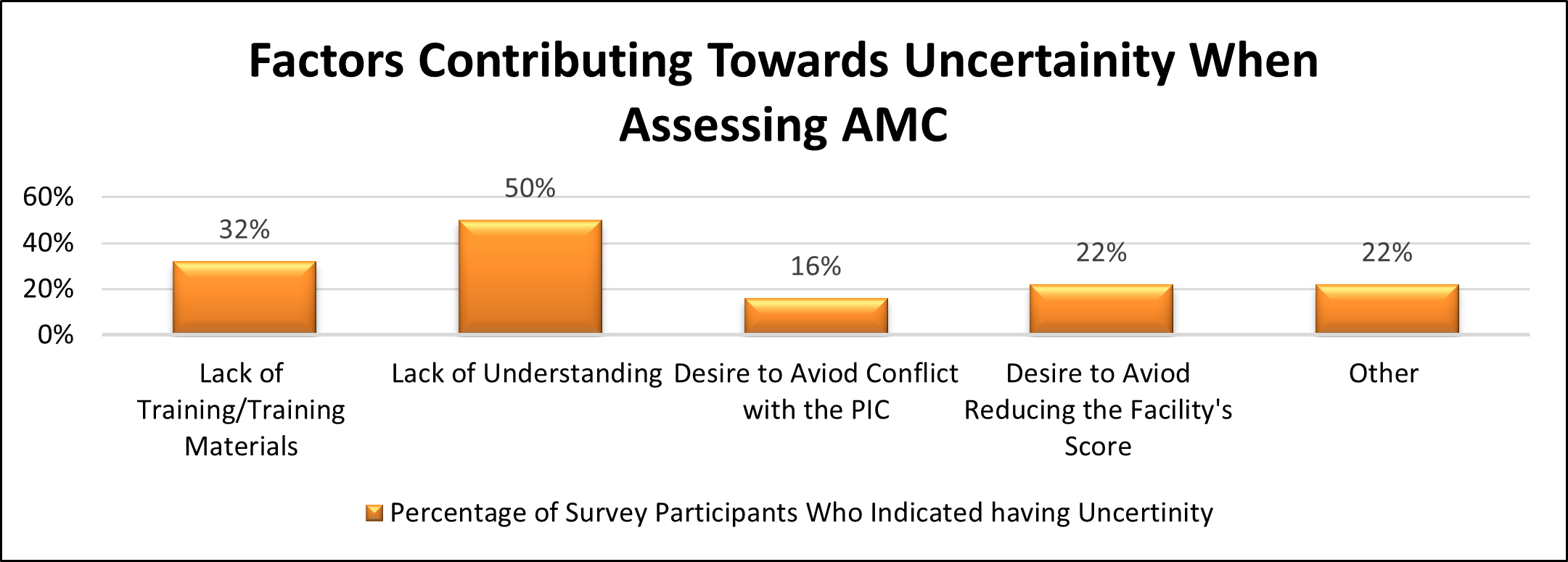

Additionally, when asked to do a self-evaluation regarding their own ability to appropriately assess AMC, 68% of participants (92) responded that they believed they were appropriately assessing AMC during routine inspections. The remaining 32% of survey participants (43) indicated that either they did not believe, or they were unsure if they were properly assessing AMC. Graph 4 illustrates the underlying reasons EHS identified as contributing to their uncertainty when assessing AMC, with lack of understanding being the most highly reported contributor.

Graph 4

Factors Contributing Towards Uncertainty When Assessing AMC

Regarding proposed actions that should be implemented, 73% of survey-takers (98) indicated that targeted training regarding how to assess AMC should be offered at the state and local level; 62% (84) indicated that concrete details should be added to the marking instructions describing when to mark item 1-2A out of compliance; and 59% (80) indicated that a supplemental training document should be developed for EHS to use when assessing AMC.

Conclusions

Analysis of the collected data led to the following conclusions:

1. While risk-factor violations were observed during 50% (57,973) of routine inspections conducted during the specified time frame, inspection data indicated that the assessment of the PIC performance of duties, as it related to AMC, was underassessed during routine inspections, as AMC was only marked “out of compliance” during 2% (2,265) of inspections.

2. Over the course of the specified time frame, data showed a 2% increase in repeat violations which could be inferred as missed opportunities to thoroughly discuss process gaps and long-term corrective actions with PICs during routine inspections.

3. Although 68% of survey participants (92) self-reported properly assessing AMC, data showed that risk-factor violations were commonly observed, and the occurrence of repeat violations continuously increased, pointing to a lack of follow through while evaluating AMC.

4. Uncertainty when assessing AMC was self-reported by 32% of survey participants (43). Fifty percent (50%) of the identified subset attributed their uncertainty to a lack of understanding, which led to increased subjectivity as EHS were relying upon their own understanding of how to assess AMC.

5. While EHS reported receiving multimodal training regarding AMC assessment, the varying definitions for “pattern of noncompliance” and “obvious failure of the PIC to ensure risk factor compliance,” coupled with the commonality of risk-factor and repeat violations, demonstrated that training received by EHS should be evaluated for effectiveness.

6. EHS seek to properly assess AMC and highly request the following interventions to better prepare them for AMC assessment: AMC focused training; the addition of descriptive language regarding AMC to marking guide instructions; and the creation of supplemental job aids.

Recommendations

This research led to the following recommendations:

1. Georgia’s marking guide instructions should be amended to include concrete language regarding the assessment of AMC as it relates to PIC performance of duties. This added language should describe both pattern of noncompliance and obvious failure of the PIC to ensure compliance.

2. To establish consistency and standardization when assessing AMC an evaluation of the effectiveness of the training received by EHS related to the assessment of AMC is needed.

3. Supplemental assessment documents should be developed for EHS to utilize during routine inspections to assist with the assessment of AMC.

4. An evaluation of how EHS are assessing AMC should be added during district uniform inspection audits conducted by district standard trainers.

5. To improve confidence when assessing AMC, additional research would need to be conducted to determine what interventions would be appropriate to address the lack of understanding reported by environmental health personnel.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge and thank each of the following for their contribution to making the journey rewarding and unforgettable:

· Dr. Lawton Davis, Coastal Health District Medical Director, Dr. R. Chris Rustin, Chatham County Health Department (CCHD) Administrator, and CCHD Environmental Health team for supporting my aspirations to participate and allowing me the time needed to fully commit the IFPTI fellowship program.

· Shaun Bryant, DPH Environmental Health Food Service Program Director and Tim Callahan, DPH Environmental Health Evaluation and Support Program Director for invaluable input and support while completing my research.

· IFPTI mentors, faculty, staff, especially Doug Saunders and Kathy Fedder, and each of the Cohort X fellows for their guidance, feedback, and support as completion of this process would not have been possible without them.

· Lastly and most importantly, I extend my sincerest gratitude to my husband, Antonio; our children, Amari and Ayrica; my parents; and my niece for their continued support and encouragement throughout this process.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Estimates of foodborne illness in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Highlights from the 2017 surveillance report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/fdoss/annual-reports/2017-report-highlights.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks, United States, 2017, Annual Report. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/fdoss/pdf/2017_FoodBorneOutbreaks_508.pdf

Georgia Department of Public Health, Environmental Health Section. (2019, April 10). Instructions for marking the Georgia food establishment inspection report form: Rules and regulations food service chapter 511-6-1.

Georgia Department of Public Health, Environmental Health Section. (2020). Rules and Regulation Food Service Chapter 511-6-1.

King, H. (2020). Food safety management systems: Achieving active managerial control of foodborne illness risk factors in a retail food service business. ResearchGate.DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-44735-9

King, H. (2016). Implementing active managerial control principles in a retail food business. Food Safety Magazine. https://www.food-safety.com/articles/6212-implementing-active-managerial-control-principles-in-a-retail-food-business

Marks, J. W. (2021). Medical definition of foodborne disease. MedicineNet. https://www.medicinenet.com/foodborne_disease/definition.htm

U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2017). Annex 4. Management of food safety practices–achieving active managerial control of foodborne illness risk factors. Food code Annexes 2017.

Author Note

Lauren Baker-Newton, MPH, REHS, Environmental Health Specialist V

Chatham County Health Department

This research was conducted as part of the International Food Protection Training Institute’s Fellowship in Food Protection, Cohort X.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to:

Lauren Baker- Newton, MPH, REHS, and Chatham County Health Department

1395 Eisenhower Dr., Savannah, GA 31406

Lauren.Baker-Newton@dph.ga.gov

Funding for the IFPTI Fellowship in Food Protection Program was made possible by the Association of Food and Drug Officials.